9th Street Stock Exchange

9th Street (Italian Market) Philadelphia, 2016

Project Website (Mural Arts Philadelphia)

Curator: Theresa Rose

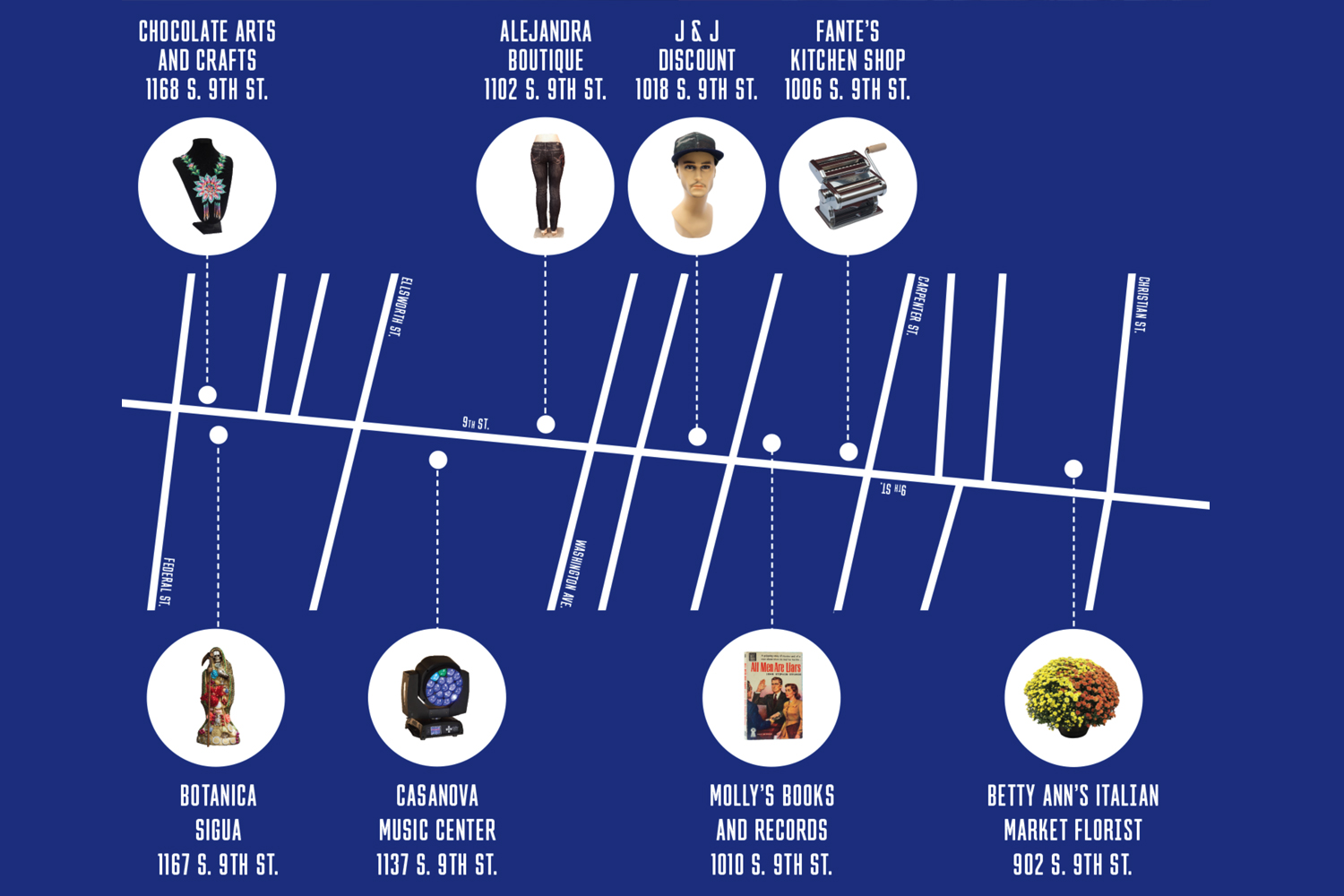

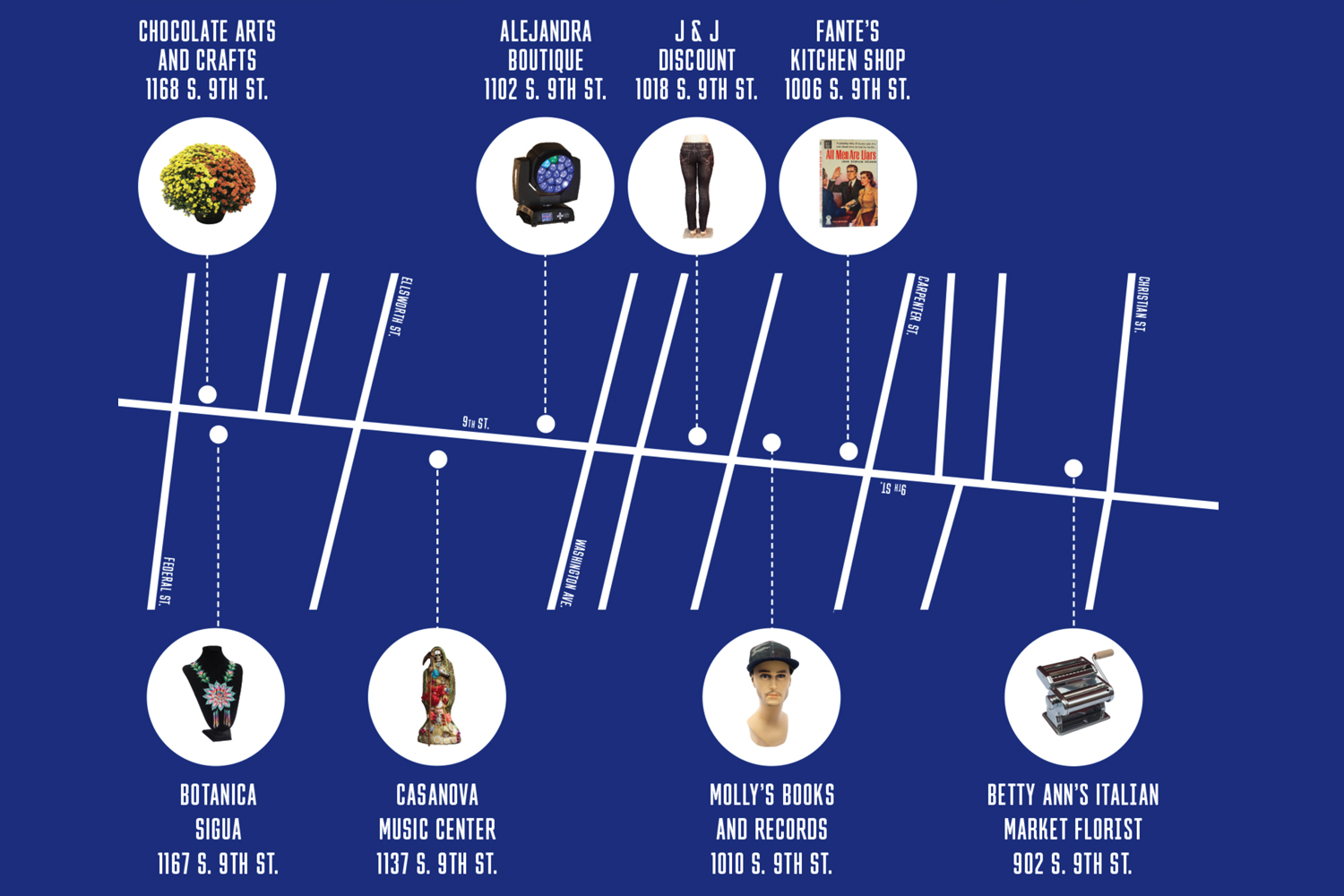

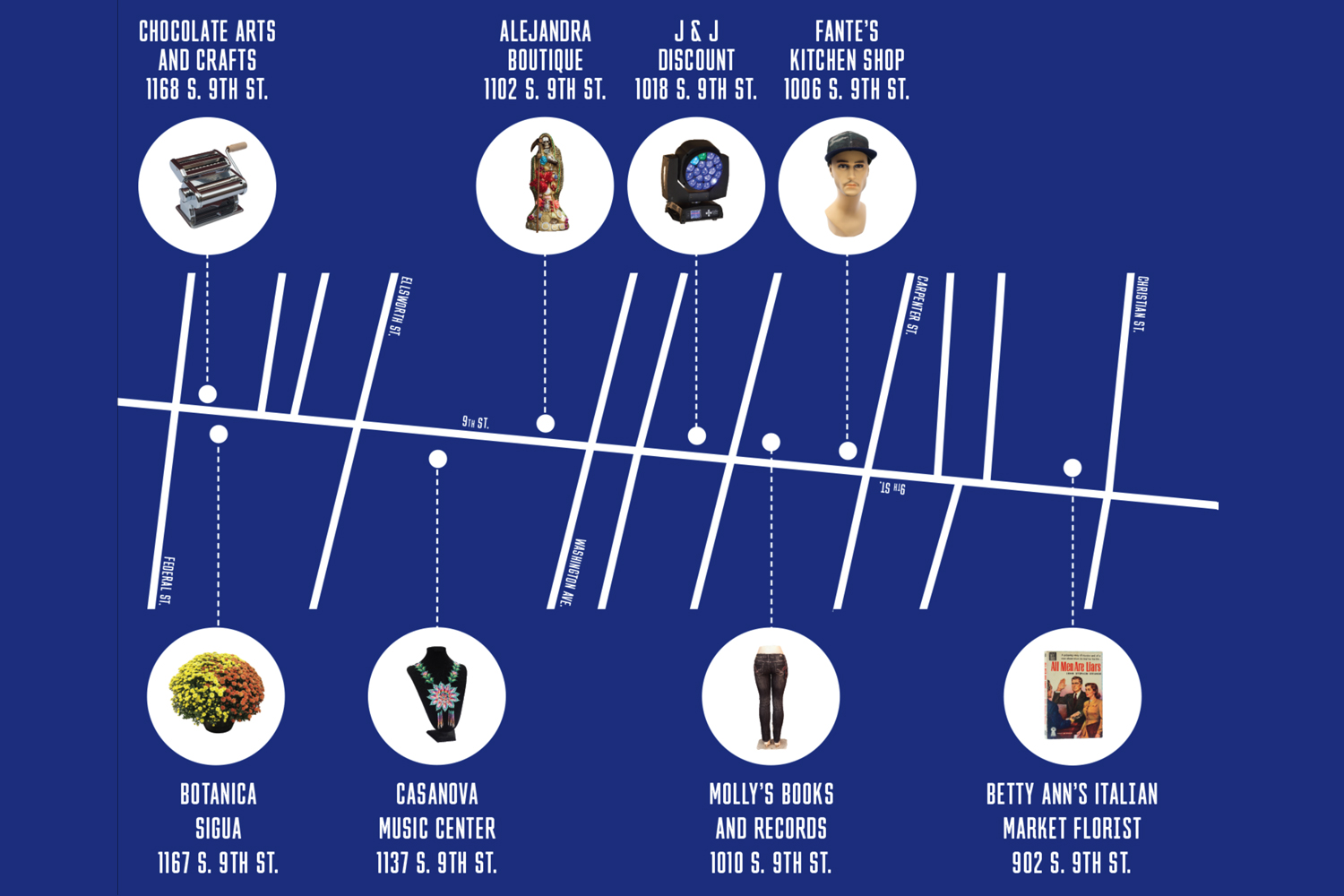

Staged in Philadelphia’s famous “Italian Market,” the 9th Street Stock Exchange was an alternate economic system that connected recent immigrant and long established businesses that operate in close proximity to each other but are often separated by cultural and socioeconomic differences. Rotating weekly, over eight weeks, the eight participating stores prominently displayed and sold selected products from each other’s businesses, facilitating unexpected social connections by experimentally incorporating an aspect of each other's identity and culture into their own. A circle of trust was constructed through the project as each participant business became familiar and invested in a small way in the commercial welfare of the other businesses. Products that in one store were culturally specific and expected by a regular customer base become strangely incongruous and newly present through this weekly act of dislocation.

..........

Essay by Nato Thompson

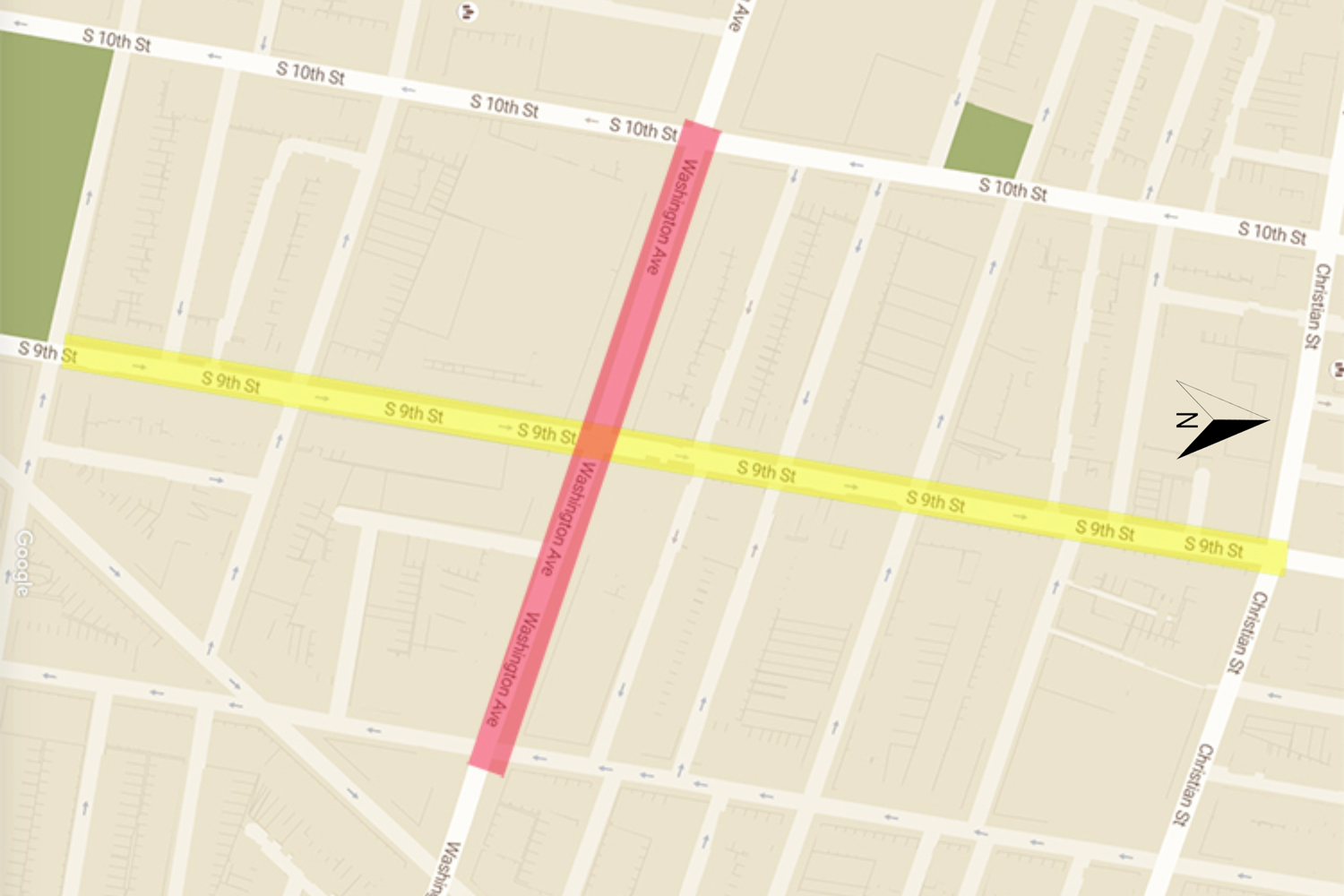

The Ninth Street Market is a magical stretch of road in the heart of South Philadelphia. A bustling, vibrant avenue of commerce, replete with fruit and vegetable stands, sea bass and trout splayed out on ice, homemade corn tortillas, cheap bundled socks, used pulp books, dusty record bins, hypnotic strobe lights, and beer bottle pinatas. It’s a living breathing people-clogging-the-sidewalk kind of market with all that comes with it. This is not Amazon.com. It’s an urban metropolitan social space where every race and class rub shoulders. With the northern end of the market geared toward Italian heritage tourism, and the southern boasting a growing number of stores from Mexico and Central America, this market is a veritable avenue of international trade and exchange. And it is in this microcosmic crucible that this subtle artwork, the 9th Street Stock Exchange, is born.

Created by Jon Rubin and curated by Theresa Rose, this project follows a fairly straightforward process in how it functions. First, a diverse set of businesses on both the North and South sides of the market are identified. Then each shop owner is approached with a series of conversations. Finally, one object for sale in their store is chosen to be exchanged and sold each week by a neighboring business. After seven weeks, there will have been seven different objects made available in each store, with 56 total juxtapositions for a visitor to see over that time. The money made from each sale goes back to the original store-owner whose objects were sold. This simple formula (which admittedly was not so simple to put into action) has a series of parts that become evident as one walks along ninth-street.

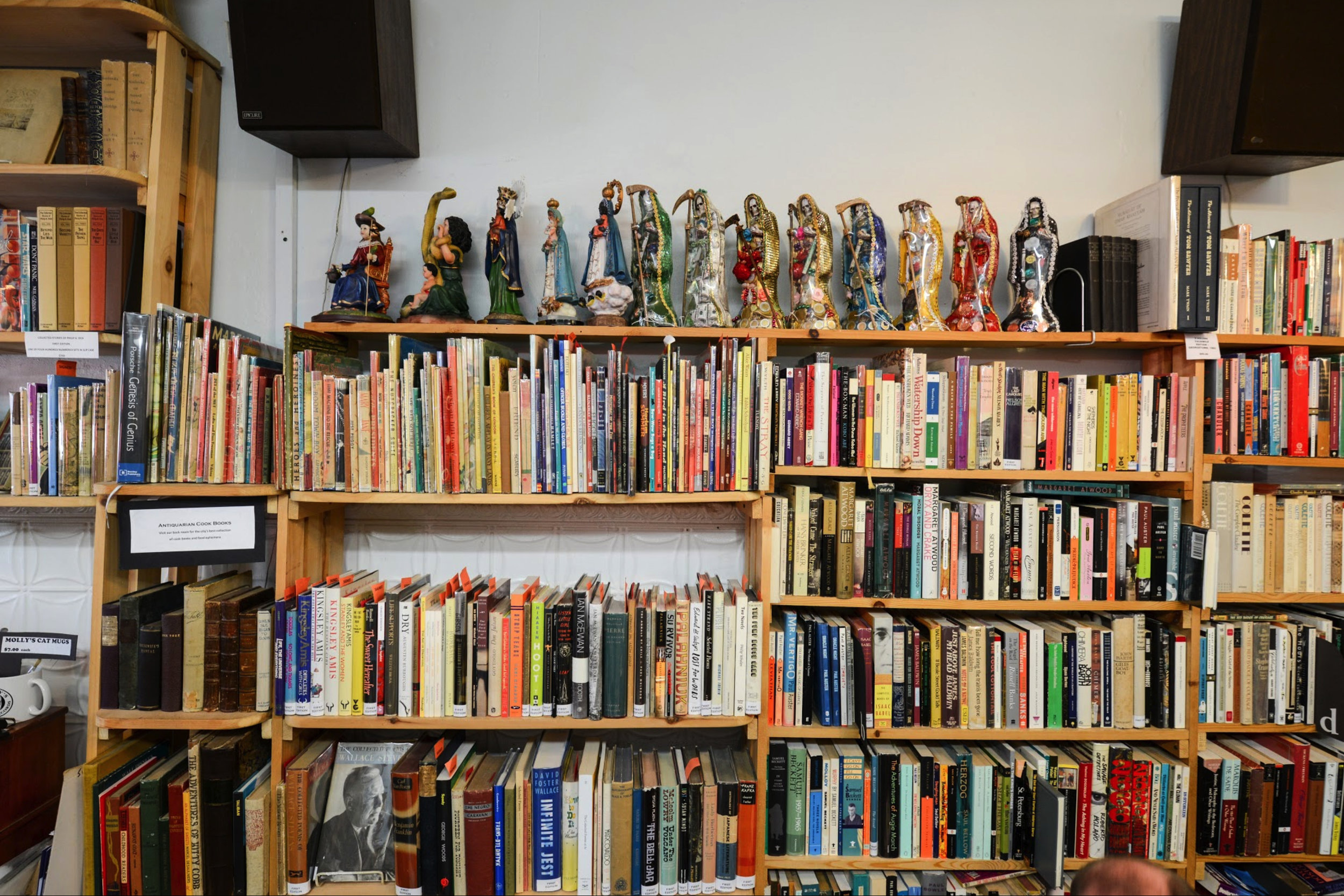

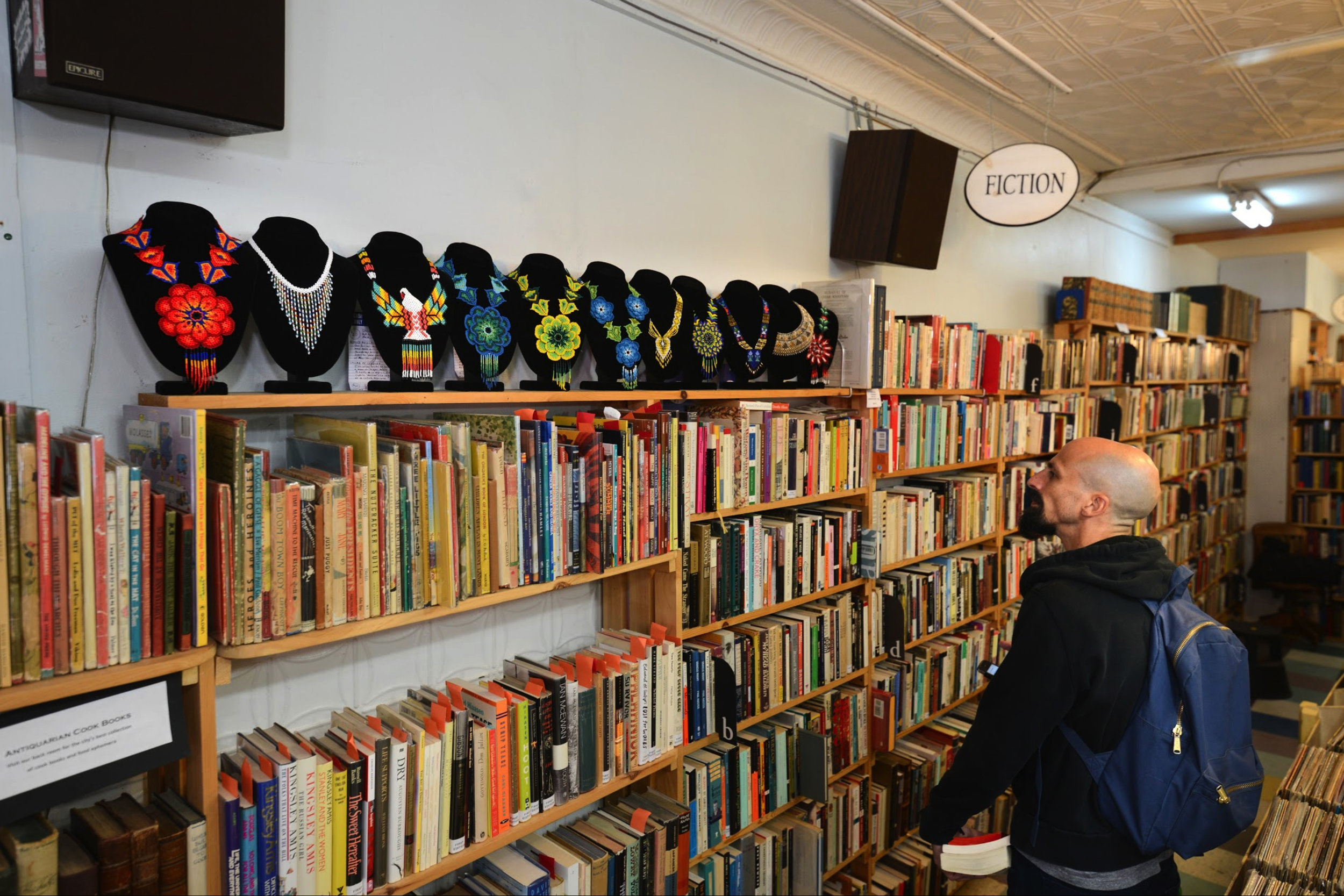

As each object weekly shifts from store to store, the entirety of this project might be best appreciated over the course of its run. Each store plays host to a new object and in so doing, sets up a new set of relationships. Great Aunt Gina’s Pasta Machine from Fante’s Kitchen Shop (established 1906) certainly has a different feeling about it when set up inside Molly’s Books and Records, a vintage bookstore filled with Virginia Woolf, James Baldwin, Richard Brautigan and old albums by the BeeGees and Thelonious Monk. And simultaneously, Molly’s selection of 1950’s pulp paperbacks of tormented love looks particularly interesting amidst the shampoo bottles and detergents in J & J Discount (a Korean family-owned sundry supply shop with basic home needs from brooms to toothpaste). Or a swirling disco light culled from Cassanova Music Shop re-presented inside Betty Ann’s Florist. What’s wrong with a little dance floor in your flower purchase? Or better, the display of five sets of female mannequin legs adorned in tight fitting Colombian push-up pants from Alejandra Boutique resituated for display and sale amongst the cookware in Fantes Kitchen Store. Yes, the exchange is subtle but revelatory and peculiar. And in exchanging, each store owner is brought into distinct relationship with each other. Not only are their products exchanged, and their individual cultural enterprises juxtaposed with each other, but also, they are literally brought into a financial agreement as well.

Each store imbues a different atmosphere, cultural composition and relationship to its products. For instance, Chocolate Arts and Crafts store, owned by Eva Hernandez. Born in Mexico, Hernandez sells items from Mexico including ceramic bowls, bright handmade jewelry, Frida Kahlo t-shirts and ponchos. Situated at the southernmost end of the market next to a shop that sells live poultry in cages, this cozy little shop brings the magic of Eva’s homeland into conversation with the rich immigrant tradition of the market itself. Just diagonal across the street is Botánica Sigua, a botanica specializing in blessed, cursed, charmed and hexed elixirs, votive, incense and statues.

While each store might appear quaint in its local Philadelphia environment, the grouping of these stores along this street creates a microcosm of larger geopolitical forces that are shaking the globe. For, as this project took off, conversations about race and trade were clearly on the minds of the voting public, elected officials, and especially President-elect Donald Trump. While Trump continues to advocate for the building of an enormous wall along the U.S./Mexican border, the mood in the country, and the focus on the undocumented workers from the Global South, has become tense along racial lines.

The question of immigration, while certainly one that became a focal point in the latest presidential election, has been part of the United States story since its inception. Of late, the conversation has shifted toward one more volatile and divisive for a multi-cultural society. Such was the political backdrop of this project. As the southern part of the 9th Street Market has become home to numerous businesses from Mexico and Central America while the northern still remains the more tourist-driven portion depending in large part on the promotion of its Italian heritage, the market is not without its racial tensions and questions. There are many other ethnicities represented in this stretch of road. This cultural schizophrenia is on display in stark fashion as the identity of the market itself is always up for grabs. Is it the Italian Market or the Ninth Street Market? As the tourist trade has doubled down on the market’s Italian identity, the actual hustle and bustle reflects a more contemporary picture of immigration as it exists.

Rather than make a direct statement on this situation, the 9th Street Stock Exchange sets sites and people into motion with each other. One cannot discuss immigration in the United States without acknowledging the manner in which questions of race are bound within a set of global and national financial markets. They are inexorably linked. So too, in this small section of Philadelphia, we find a similar set of dynamics. With a sense of collaboration, this artwork fluidly touches on economies, culture and exchange, as a subtle way to point at these larger forces shaping our national dialogue.

This style of working is not new for Jon Rubin. An early progenitor of what has come to be called “social practice,” Rubin often works with the existing world as his canvas, using social relationships as a material to shape and bend. In a 2002 project titled The Horse, Rubin opened up an ad-hoc restaurant across the street from an existing high-volume restaurant called Le Cheval. Customers to his restaurant ordered directly from a reprinted version of the Le Cheval menu. Waiters would call the order in to Le Cheval, and then Rubin would run over to the restaurant, pick it up, bring it back, re-plate it and serve it to the customers of his restaurant. The owners of Le Cheval never knew the project was going on. A simple twist in existing relationships of commerce produced an entirely new idea of what an economy might consist of.

In the 9th Shanghai Biennial of 2012, Rubin purchased the entirety of an estate sale from a Pittsburgh family, the Lovasiks. Purchased for a mere five thousand dollars, the entire belongings of the Lovasik family (including photo albums, furniture, souvenir mugs, jewelry and even a dishwasher) were shipped to Shanghai for this major international exhibition. Each item in the estate sale was set up exactly as it was in the home. Over the course of the exhibition, visitors purchased objects from the estate and immediately took them home. The installation essentially dissolved as the exhibition continued, selling off the final object on the last day of the Biennial. This sprawling large-scale artwork was reminiscent of a flea market, with visitors from China perusing items and experiencing an art show from a peculiar lens of commerce, nostalgia and redistribution. It’s important to note that over half of the objects in the estate were originally manufactured in China for American consumers. Each day, when visitors in Shanghai purchased possessions from the estate and took them home, they were essentially repatriating these objects into a market for which they were never intended.

What makes Rubin’s practice so fascinating is that it reveals how malleable our existing relationships are. This simple insight, that the way we commonly navigate the world can be manipulated and shifted, is one of the lingering and definitively political parts of his work. By using the way one navigates the world (whether it is ordering food, buying goods at a flea market or shopping in the 9th Street Market) as a medium akin to clay or paint, Rubin demonstrates a skill set that can be utilized by anyone. Understanding that our neighborhoods are places that can be shaped, from the way we exchange to the way we interact with each other, can make it possible to imagine new, more dynamic, social relationships in our own communities. As one of the founders of the Happenings, the art performance gatherings in the 1950s, Allan Kaprow once wrote, “A walk down 14th Street is more amazing than any masterpiece of art.”

Another interesting foil for this project is Marcel Duchamp’s conception of the readymade. A readymade artwork is constructed by simply repositioning an existing object in order to see it in a new light. In the early 21st century, Duchamp collected a few pre-existing manufactured products including a bottle rack, a snow shovel, a coatrack, and most famously a urinal, and displayed them as artworks. At times, he would modify them by showing them upside down, or adding his name as a signature; while in other instances, all he did was re-contextualize objects by placing them in a museum. In either case, the art that took place occurs in the viewer’s shifting understanding of these objects: from one that is naturalized and disappears into the background, to one where these fairly normal objects are suddenly brought into relief and focused on.

In the 9th Street Stock Exchange Rubin also works with readymades, but rather than simply objects, his readymades are also social relationship. And to further complicate matters, he works not in a museum, but in the existing world. In essence, he returns the readymade to the world, but with the slightest tweak. Unlike Duchamp’s readymade, in which objects are juxtaposed to the stark white walls of a museum, in Rubin’s artworks that take place outside the museum, these objects are juxtaposed to already existing social environments. In this way, they are camouflaged by the surrounding retail environment, and can almost disappear yet again into the normality of what we accept as the typical social composition of life. But when one focuses their eyes and acknowledges the jarring juxtaposition of these readymades into their new environs, one witnesses how the smallest intervention creates new possibilities for sociality, commerce and exchange. Suddenly what is readymade and naturalized is undone, remade, and opened up for interpretation.

The 9th Street Stock Exchange took a marketplace as its canvas and worked with the given environment to produce an altered set of social relationships. Rather than wondering if it is art or not, or whether or not it is beautiful, it is perhaps more helpful to consider what this intervention opens up for us in our own imaginations. What other collaborations are possible? What new forms of business? Can we imagine other kinds of market places? In asking these questions, we gain insight into how we can collectively shape the world we live in.

..............

Article for the Philadelphia Inquirer by Nancy Chen, Stock Exchange Turns Italian Market into Art

..............

Bilingual Project Coordinator: Tim Gibbon

Graphic Design: Alex Lukas

Photography: Mike Reali and Steve Wienik

Participating businesses include (listed north to south):

Betty Ann’s Italian Market Florist, 902 S 9th St

Fante’s Kitchen Shop, 1006 S 9th St

Molly’s Books and Records, 1010 S 9th St

J & J Discount, 1018 S 9th St

Alejandra Boutique, 1102 S 9th St

Casanova Music Center, 1137 S 9th St

Botánica Sigua, 1167 S 9th St

Chocolate Arts and Crafts, 1168 S 9th St

Funded by John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Mural Arts Philadelphia, the City of Philadelphia